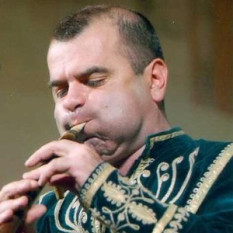

Armenia is situated close to the Caucasus Mountains, and its music is a mix of indigenous folk music, perhaps best-represented by Djivan Gasparyan's well-known duduk music, as well as light pop, and extensive Christian music, due to Armenia's status as the oldest Christian nation in the world.

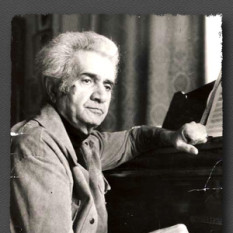

Armenian folk music is one of the world’s richest musical traditions, burgeoning with an extraordinary array of melodies and genres. Since the 1880s, ethnographers and musicologists, most famously the Armenian priest Komitas Vardapet, have travelled to remote villages and towns in Anatolia and the Caucasus collecting Armenian songs and dances. Currently there are over 30,000 catalogued in various archives, each with rhythms and modes characteristic of both broad Near Eastern influence and particular rituals and dialects not seen or heard beyond the next mountain pass.

In the city of Erzerum west of Mt. Ararat one would most likely dance to a 10/8 rhythm, as do Turks and Kurds in the area, while across the Transcaucasian region, shared by Georgians and Azeris, a fast 6/8 is typical. Folk instrumental ensembles heard to the west might include the ud, while the duduk is the main folk instrument to the east, where melody is always accompanied by a drone that holds the tonic note. Such musical differences solidified in the wake of the genocide of 1915, in which over a million Armenians perished and the remainder fled either to the West or eastward to what would become a few years later the Soviet republic of Armenia, today an independent nation.

Armenian folk music, forged over centuries in the language and rituals of everyday life, traditionally accompanied everything from family celebrations to sowing fields to funerals, and remains a rich brew of historical elements. Pagan ritual can still be traced in songs foretelling a maiden’s future retained as part of the Christian festival of the Ascension, not to mention the beloved circle-dance, with its prehistoric and Zoroastrian antecedents in the Near East.

The folk repertoire is in many cases highly differentiated—specific songs, each with distinct modal characteristics, are tied to dozens of moments in the wedding ceremony, from blessing the wedding tree to the entry of the bride to male-only dances. As in much of the Middle East, Armenian music is modal, based not on an octave with major or minor notes, but on an untempered scale. Still, repertoire from the Anatolian plain differs from that found in the Caucasus mountains, and within these areas distinct folk music styles, rhythms, genres and instruments evolved corresponding both to the main geographical and political division of Western and Eastern Armenia and to the more than 60 regional dialects spoken across this vast expanse.

Occupiers and merchants invariably introduced new customs, and Armenians were adept at assimilating and transforming neighboring traditions, from Persian Zoroastrianism with its worship of fire to Roman bureaucracy to Central Asian and Middle Eastern musical instruments.

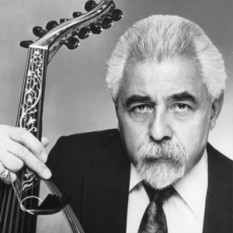

The elaborate modal music of the liturgy was theorized in writing and notated as it developed, becoming part of an intellectual clerical tradition that remained cohesive for centuries. Meanwhile Armenia’s remarkably stable feudal courts and large towns and cities supported professional bardic ashughs who prospered especially between the 17th and 19th centuries travelling from town to village singing of Armenians’ historical feats and forsaken love.

This wealth of folk material was honed and passed down over many generations, its depth a result of the Armenians’ long historical presence at a remote, biblical crossroads of the world.

Speaking their own Indo-European language and following their own kinship and religious traditions, they formed a unique culture that thrived through centuries of conflict and usurpation. Sandwiched between the Graeco-Roman and Persian empires in the classical period and the Ottoman and Russian empires in the modern period, and for years a valued trade route on the Silk Road, Armenia was continually reconquered, divided, governed and taxed by invaders, spawning a large diaspora as early as the Byzantine era.

.